Our experience makes us think that the alarm clock of our smartphone is essential to start our day on time. However, who did never experience the condition of forgetting the alarm off and still waking up at the usual time, sometimes even no matter at what time we went to bed? Light, hormones and circadian rhythm are the “ingredients”. Indeed, another alarm clock – less technologically sophisticated, but trained from millennia – based on light and hormones, permanently active in each of us.

INDEX:

1. The circadian rhythm

Our organism possesses an internal biological clock – the so called circadian rhythm – able to regulate sleep and wakefulness. A clock with a 24-hour period modulated by a set of factors, first of all light and darkness.

When the retina in our eyes is excited by light, it transmits the signal to specific areas of our brain which in turn activate the release of a series of excitatory modulators that stimulate the nervous system, muscles, heart and other organs, preparing us to wake up.

On the other hand, darkness stimulates the synthesis of inhibitory modulators with soporific and relaxing action.

2. The modulators of rhythm

The main modulators of the sleep-wake rhythm belong to two classes of molecules – neurotransmitters and hormones – that once released in response to an appropriate stimulus produce a cascade effect on the body:

- Hormones are produced by our body’s endocrine glands and then released into the bloodstream where they act as chemical messengers transferring instructions from one cell to another;

- Neurotransmitters are the endogenous chemical messengers exploited by our neurons to communicate with each other and with both muscle and gland cells.

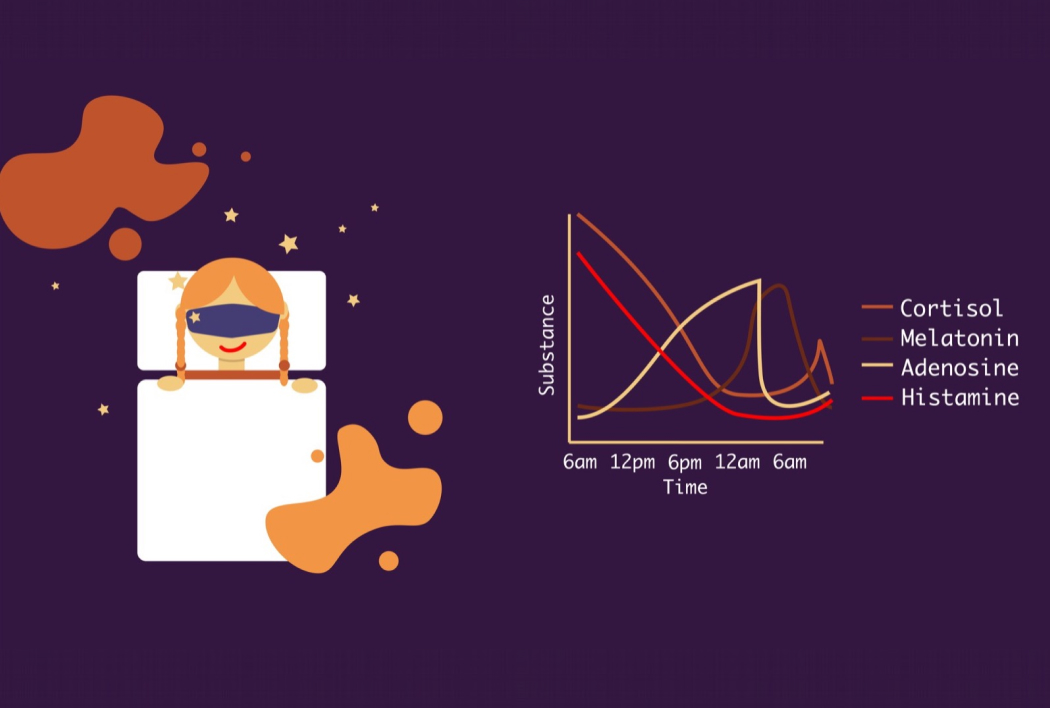

Four main modulators of the sleep-wake cycle have been identified1. All of them are produced by the central nervous system, which prepares for nighttime rest already in the middle hours of the day, just when we are busy at performing daily activities.

During the waking state our brain consumes a lot of energy producing a series of waste molecules such as adenosine, an inhibitory neurotransmitter called “the substance from which sleep originates”. Throughout the waking hours the levels of adenosine increase, in turn stimulating particular brain receptors and activating a mechanism of drowsiness. A warning signal from the brain that pushes us to stop and rest.

Another mediator of sleep is melatonin, a hormone produced by the pineal gland, a small endocrine gland located in the center of the skull. Melatonin production occurs in response to darkness, reaching a peak around 2 a.m. and then gradually decreasing until dawn, when cortisol levels start to rise instead.

Cortisol, known as “the stress hormone”, has an opposite action to that of melatonin, inducing a state of “alert” in the body: it signals us that it is time to get active and face a new day. Its production takes place in the hypothalamus, which receives information from the nervous cells of

the retina.

In the hypothalamus it is also produced histamine, a hormone that like cortisol contributes to wakefulness by leading neurons closer to the threshold of excitation. For this reason, if you have ever taken antihistamine drugs you will have experienced a sense of drowsiness!

Trend of the major sleep-wake rhythm modulators throughout the day

3. Impact on health

The slogan “sleep is good for your health” is not accidental. Contrary to what we may naturally think, when we sleep we do not “switch off” completely, but we carry out a series of functions that are essential to preserve our organism.

A misaligned sleep-wake cycle can therefore alter our psycho-physical health state.

As shown by a study by the National Sleep Foundation2, both the quality and quantity of hours spent sleeping are important.

The minimum number of hours of sleep per day for our body to function properly varies with age:

- infants (0-3 months): 14 to 17 hours;

- preschool children (3-5 years): 10 to 13 hours (never less than 8);

- school-age children (6-13 years): 9 to 11 hours (never less than 7);

- adolescents (14-17 years): 8 to 10 hours (never less than 7);

- adults (17-65 years): 7 to 9 hours (never less than 6);

- seniors (over 65): 7 to 8 hours (never less than 5).

Unfortunately, however, our frenetic and busy lifestyle increasingly reduces the time dedicated to sleep.

It has also been estimated that currently about 60% of the worldwide population suffers of a low quality of sleep3.

This can generate toxic effects on our organism4, including:

- increased weight, due to an increase of ghrelin and a decrease of leptin, the two hormones that respectively stimulate and inhibit appetite;

- increased risk of cardiovascular diseases;

- impaired immune function;

- Increased risk of mental health problems, such as depression;

- reduced capacity for social interaction.

In this case, prevention is not only better, but also more simple than cure: not to push the internal clock that Nature gave us would be enough.

Miriana Povolo – science communicator @Nabu Creative Studio

References:

- Normal sleep and circadian rhythms: Neurobiologic mechanisms underlying sleep and wakefulness. Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior Faculty Papers. 2006.

- National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015

- Are you sleeping enough? This infographic shows how you compare to the rest of the world, Word Economic Forum. 2019

- Circadian misalignment and health. International review of psychiatry. International Review of Psychiatry. 2014